What follows is the sermon I preached on June 7, 2025 at Kilmarnock United Methodist Church in Kilmarnock, Virginia at the service of death and resurrection for my father, Walter Mitchell Forrester.

My name is Doug Forrester and I am dad’s oldest son, or as he likely introduced me to you, “the one who is the preacher.” For the last twenty-eight years, I have served as a pastor in the Virginia Conference of the United Methodist Church, most recently as the superintendent of the Valley Ridge District in southwest Virginia. I would like to begin this afternoon by giving thanks to the Rev. Chris Watson, the pastor of Kilmarnock United Methodist Church, for the care and lovingkindness he has demonstrated towards my family over the course of the last several months and for the grace he has shown in allowing me to stand behind this sacred desk and fulfill dad’s expressed desire for me to preach this service.

For ten years, I served as a member of the conference Board of Ordained Ministry. One of my responsibilities was to serve on the interview committee called “Practice of Ministry,” which includes preaching. In this capacity, I was part of the evaluation of the preaching of over one hundred women and men seeking commissioning and ordination in the United Methodist Church. I tell you that only to say that without question, the greatest sermon I have ever heard in any context on the topic of the resurrection of the dead is the one preached by my brother Michael, in those final hours, as he walked dad to the door separating life from life everlasting, as he held our father’s head in his hands, looked into his eyes, and assured him that the next place is better, that God will care for those of us who remain on this side of the door, and that the saints of God who dad loves and who love him awaited him across the threshold.

All of this is to say that I pray that this sermon measures up as much as it can. It is also to say that, Michael, I still have a couple of open local church appointments on the Valley Ridge District that I would love to talk to you about after the service.

It is so important for members of any local church of any denominational or non-denominational stripe to pray for those whose vocation it is to preach the word of God. It is foolishness for anyone to be so bold as to believe we posses an ability even begin to articulate the glory of the divine, and yet Sunday after Sunday, we still try. So then, I humbly request that you pray for me in what stands before me now. As an incentive, I promise you that if I can get through this, I will tell you at the end of this sermon my father’s very favorite joke, one I believe that if you knew him, you will love as much as he did.

When we were growing up in Richmond, dad was fond of saying that the way he wanted to die was to live to be ninety-nine and be killed by a jealous husband.

I still have no idea what this means.

He was also fond of saying that if it turned out that reincarnation is real, he wanted to come back as one of his bird dogs or one of his children, because be believed he had been good to both.

He was right.

Dad was born in a house in Browns Store, Virginia on February 25, 1936. Having Browns Store on his birth certificate was a source of pride for him; “How many people do you know who have Browns Store on their birth certificate?” he used to say. As a boy, he was a remarkably gifted athlete who ran track and played baseball and basketball. He loved to drive around the Northern Neck and regale Michael and me with stories of his athletic achievements, including the time he scored over 70 points in a basketball game.

“I would have scored 100, but the coach took me out, so as not to embarrass the other team.”

He would drive past long-abandoned baseball fields, now converted back to farmland, and tell us about the home runs he had hit: “One time, I hit a ball over those tall trees from right back there by the road.” I can remember sitting there as a child in his wood-paneled Oldsmobile station wagon, so impressed that I had a father who, apparently with regularity, hit a baseball over a quarter-mile.

Dad was immensely proud of the fact that he could claim membership in the elite fraternity of Chesapeake Bay watermen. Even towards the end of his life when his speech was very difficult to understand, he still used what words he could muster to let me know how the fish boats, especially the one captained by Jimmy Crandall were doing, how many millions they had caught, how the boats found themselves having to fish further north than they did in his day.

Dad’s life was characterized by humor, grace, hard-work, industriousness, creativity, and so much love. These attributes served him well as he birthed out of nothing what would become the nationwide Best Products sporting good department, simply by talking his boss into giving him an opportunity to try to make it work at the store where he began as a clerk.

Mom and dad moved to Richmond in the 1960s as young adults to find work outside of the limited options of the Northern Neck, to marry, start a family, and raise Michael and me. Dad did well in Richmond. He managed to have a successful career in a dying industry, made friends, and was an immensely generous provider for his family. However, I do not believe he would have ever considered himself a Richmonder. His body never fully accepted the transplant. When mom and dad moved back to Kilmarnock in 1999, I called him after he had been here a couple of weeks and he told me that he was having trouble sleeping because he was could not stop thinking about all of the great things he was going to do the next day and all of the people he was going to see.

Then he told me that the day before, he had somehow managed to shoot a groundhog in the backyard without getting out of bed: “I had the gun within reach and I used the barrel to open the window. I shot him, closed the window, and then I fell back asleep.”

I believe that this was his way of proclaiming in the most ceremonial way possible, “I’m back.”

He was always remarking how his friends called Michael and me “Mitchell’s shadows.” “There goes Mitchell and his shadows,” he would tell us they had said this, saying it in a way that evidenced what a source of pride it was for him. We loved spending time with dad. His company was just so enjoyable. He would tell us stories of the rural community in which he was raised that was so remarkably different than what we knew in Richmond in the 1970s and 1980s. He let us eat anything we wanted when we were with him, and introduced us to foodstuffs we would not otherwise know, such as Vienna sausages and something called “potted meat food product.”

He was effortlessly the funniest person I have ever known, and if he picked on you, it meant he thought you were alright, even if some of his humor was at your expense. For example, he told me that the sweetest blackberries are the ones that are still half-red and that the dramamine he bought for me before we went out on the boat was chewable.

Neither of these things are true.

After I graduated from divinity school and moved to Newport News to begin my first local church appointment, I was one step away from convincing a dear friend from college to marry me. That one remaining step was to convince her that the family into which she would be marrying is not crazy. So, one day, Mom, dad, Tracy, and I gathered for lunch at the Outback Steakhouse on Jefferson Avenue. Dad sat across from me and mom sat across from Tracy.

As we waited for our order, the couple at the table beside us paid their bill and left. This was when I noticed dad attempting to be subtle as he was motioning with this head at their table. I heard him whisper “Son, son” as he tried to get me to notice what that couple had left behind. That thing was a half-eaten fried monstrosity called a “Bloomin’ Onion.” It was at this point that learned that unbeknownst to me, I had the gift of ventriloquism. I learned this because, without moving my lips, I said to him “I will drag you out of this restaurant and pummel you.”

To this, he whispered, “I checked them out. They’re clean.”

Reflecting on my life and ministry, I have come to realize that so much of what has made me good at what I do is rooted in the example dad set for me. When as a seminarian, I started visiting and shut-ins, it seemed so effortless and familiar to me. It all seemed to come naturally, like I possessed these abilities as innate gifts, but I didn’t. They were all modeled for me by my father. I did not visit the sick, grieving, and homebound because it was my job. I visited them because they were sick, grieving, or homebound, just like dad did time and time again across this community that he so proudly called home.

Dad did not like conflict, but he wasn’t afraid of it, either. Mom has remarked how they did not fight because you couldn’t get him to do it. Dad once told me how, while he was away serving in the Army, his father sold dad’s car, a 1940 Ford. Dad returned home from the service to find he no longer owned any manner of transportation.

“Didn’t that make you angry?” I asked him.

“I don’t know. I guess not,” was all he said.

The only times I ever recall my father being disappointed or angry, it was in those times when people had the chance to do the thing that was kind, generous, honest, fair, or compassionate, and chose not to, when people chose, in the words of Saint Paul, to conform to the world instead of being transformed by the redemptive power of love. It was here that his life most pointedly resembled the life of Christ. Reading the gospels, Jesus largely does not find others’ lack of faith in him and his unique relationship with God in any way as infuriating as as when people who claimed faith consciously choose to neglect the opportunities to do the right thing for others, especially people in need, even when it was the difficult thing to do.

Several times, dad told me the story of the time when he was in his executive position at Best Products and a vendor who sold pocket knives took him to lunch. Over lunch, this vendor offered dad a proposition where if Best would show favor to this man’s brand of pocket knives, he would send kickbacks directly to our house. “No one will ever have to know,” he said.

Hearing this, dad rose from the table and told the vendor that he knew what was going on here and that he was leaving.

“No! Wait! You misunderstood me!” the man said.

“I understand you perfectly,” dad said. “I was raised to only answer to one man, and I call him dad, and he raised me better than this.”

By itself, that is a pretty impressive story, but it does not end there.

“It took me ten years, but I got every single one of that man’s knives out of every Best Products store in the country,” he told me.

For the majority of the time when dad was working for Best Products, the corporate office was on Route 1 just north of Ashland, which meant he had a roughly thirty-minute commute each way from our home in the far West End. He rose early, worked hard, and came home late. As Michael and I grew, he became frustrated with the fact that after a certain point, coaches in the Tuckahoe Little League were not required to allow each player on the team to play in every game. He became so incensed that kids were expected to attend every practice, only to watch from the bench the other kids play that he took matters into is own hands and become a coach, my coach, guiding our practices even after those long days in his corporate job.

When he decided to do this, he sat me down and told me that I was no longer going to start every game or play all nine innings. This “everyone plays” rule was going to affect me as well. His plan worked in the sense that every player on the team got on the field. However, it did not work well in the sense of our win-loss record. Think last year’s Chicago White Sox and you will have and idea of what I am talking about. One day after we had lost yet another game, we got in this car to ride home and I let him have it. I was so sick of losing again and again and laid it all at the feet of his unorthodox coaching style, one clearly not encumbering all those teams who were trouncing us.

That is when he told me “Son, there are things in this life more important than winning.”

“Do not be conformed to this age,” Paul writes, “but be transformed by the renewing of the mind, so that you may discern what is the will of God—what is good and acceptable and perfect.”

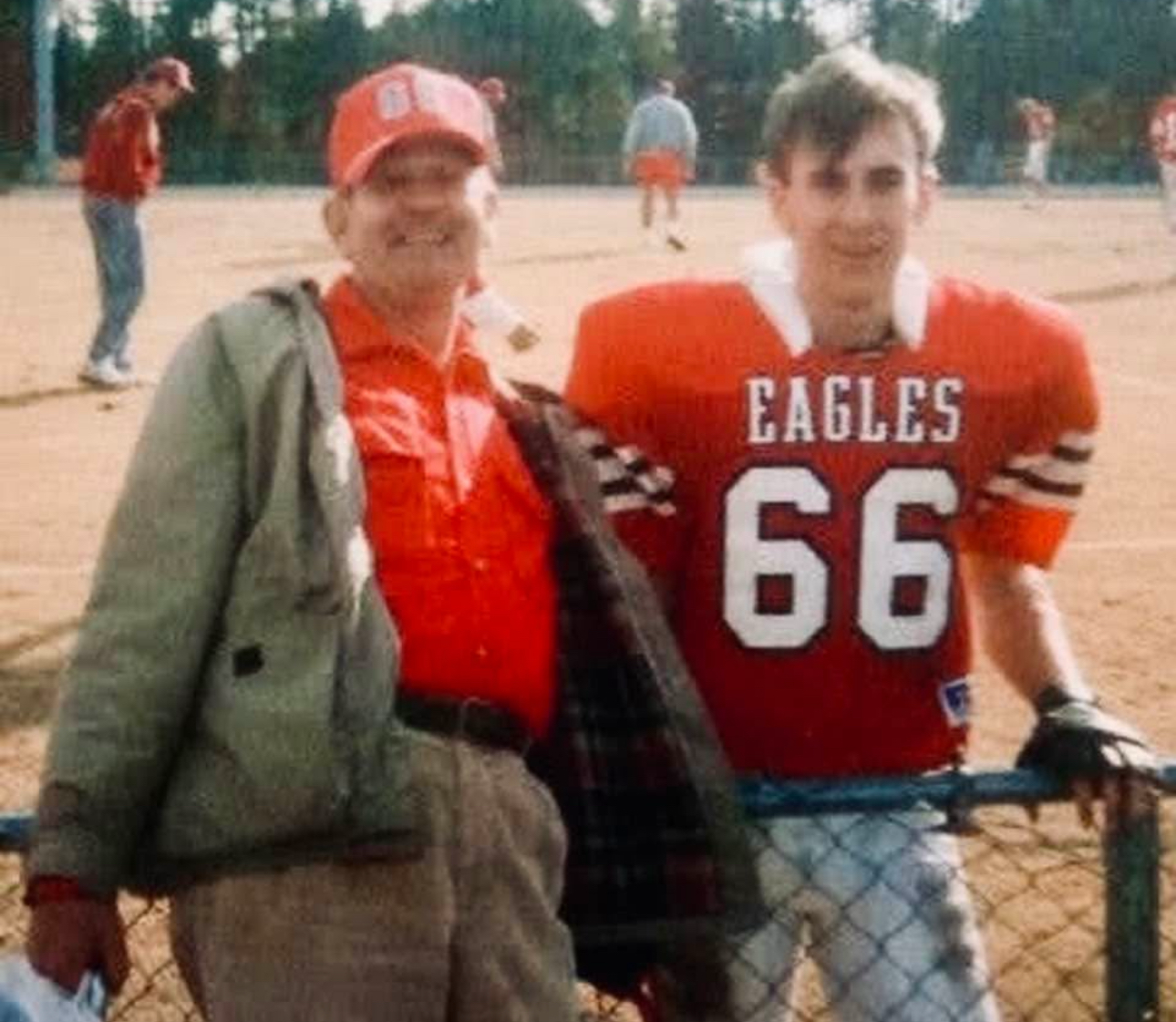

Perhaps dad’s greatest spiritual gift was encouragement. Throughout my life, he never stopped telling me how proud of me he was. When I was in high school and playing football, my school was playing for the regional championship at City Stadium, where the University of Richmond played, when late in the game, I blocked a punt that landed in the end zone where I could land on it and score a touchdown. That touchdown put the game far enough out of reach for our opponents that, in many ways, I was able to honor dad with it because our coaches could now, with victory in hand, take out the starters.

Or to put it another way, everyone got to play that day.

This was 1988, and back then, video cameras were rare, but our coaches had someone filming the game for us to study as we prepared for the next game, and my coach gave me a copy. There were probably over 1,000 people at that game, but in the audio of that videocassette, all you hear is dad shouting “Go hard, big man, go hard!”

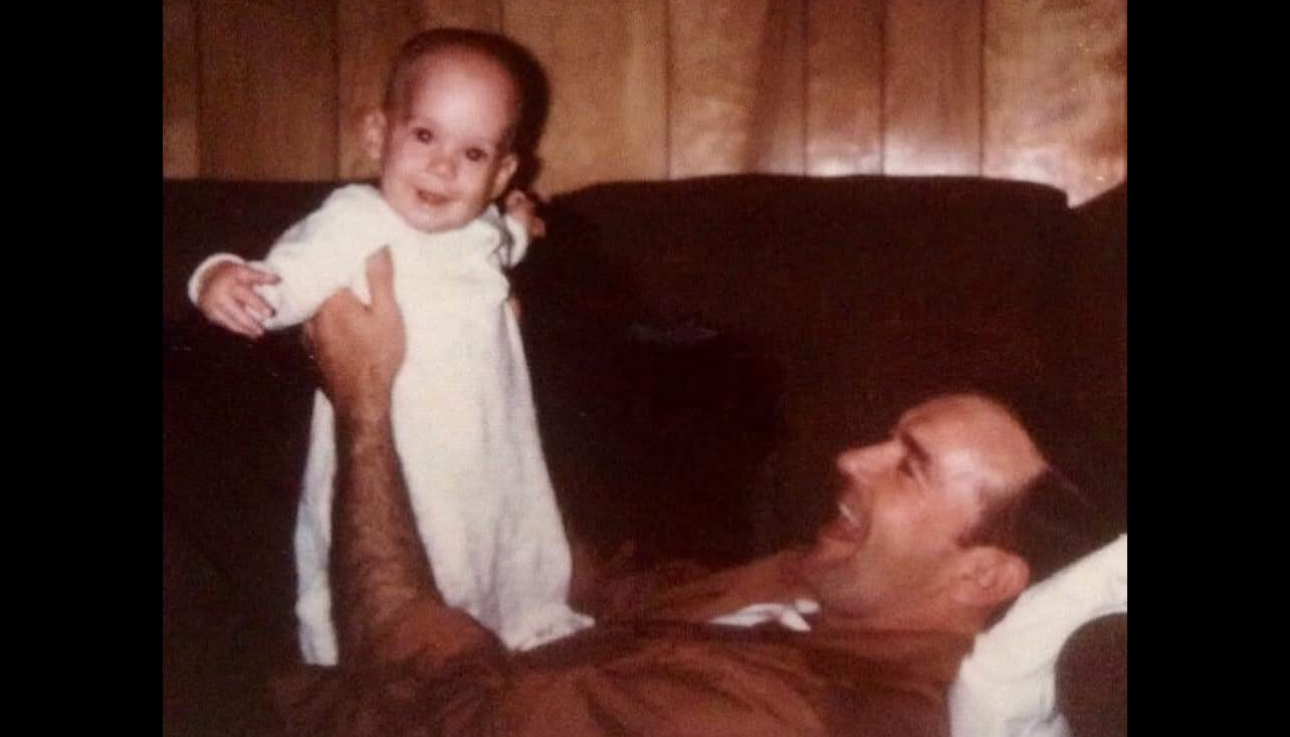

Throughout my life, when I was little, when I was a teen, when I was in college, dad would look at me and remark, “You will never know how much I love you until you have one of your own.” Over time, this was shortened to a simple shake of the head and “You’ll never know.”

Just after midnight on April 13, 2002, at Mary Immaculate Hospital in Newport News, I became a father when my daughter Ellen was born. After her birth, it was time to take her to the nursery so that she could be cleaned, measured, weighed, and put beneath one of those infrared French fry lamps to keep her warm, and it was decided that dad and I should go together, so we did.

We stood there, just the two of us, in the middle of the night looking at Ellen who was, in that moment, the most beautiful thing I had ever seen in my entire life, with her pointy head and those anime eyes. As we did, dad looked at her, and then looked at me and said, “And now you know.”

And then he said, “You know, tomorrow is the first day of turkey season, and I’m here. But if you have another one, can you work with me a little bit?”

The great cruelty of the disease that took dad is that over time, it took so much from him. It took his mobility, his ability to eat (something he truly loved), and eventually, his ability to speak. For years, he was able to jerry-rig handles and other contraptions which allowed him to get from point A to point B and have some measure of quality and variety in his life. Dad could not build or fix anything but he could rig anything as a practical byproduct of his characteristic ingenuity. Most illnesses could be treated with Absorbine Junior. Most things could be repaired with bailing wire and duct tape, and when zip ties were invented, there was no stopping him. When he was working for Walmart he learned that he no longer needed to purchase eyeglasses. There was always something in the lost and found with a prescription that was close enough. When he hurt his shoulder, he just stopped by the office of his dear friend, Dr. Joe Taylor.

Never mind that Joe was a veterinarian. “Don’t dogs have shoulders, too?” Dad said.

After mom and dad had been back in Kilmarnock for a few years, Tracy, Ellen, Claire, and I visited mom and dad, and as we were seated for dinner, Dad proudly announced “I ate nine ears of corn for supper last night. Nine. It was my whole meal; nothing by corn.”

I asked mom, “Why did you give him nine ears of corn?”

She simply replied, “He kept asking for it.”

As silly as that story is, it is such an apt metaphor what was to come. Oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy, or OPMD, is a rare genetic disorder that in western nations has a prevalence of about 1 case for every 100,000 people.

And I can tell you that if he ever had heard that statistic, dad would have made a joke about him being one in a million.

As rare as this disease is, it is not rare on dad’s side of my family. As it does for many, if not most people with OPMD, dad’s symptoms began with drooping eyelids and difficulty swallowing and, over time, moved to his extremities, which eventually left him more-or-less bedridden before leaving him completely bedridden. In the summer of 2021, he fell and fractured his pelvis, an injury that served to hasten the limitations that the OPMD would foist upon him. Thinking it would keep him safe from aspirating food for the short time he had left, the hospital provided him with a peg tube which would be his sole source for hydration, nutrition, and medication for the rest of his life.

This all led to a profound example of the scripture that reminds us that “the Lord works for good through all things for those who love him and are called according to his purpose,” because the rest of dad’s life was not a few days, weeks, or months, but four years. These four years were made both livable and memorable thanks to the gifts and generosity of Bay Aging Veteran Directed Care, Jimmy Crandall – my brother from another mother, the man who never did anything on a boat that dad did not share with me, dad’s dear cousin and loving pal, June Turnage, John Bersik, Barbara Merolli, Faye Wright, Dr. June Daffeh, Jen Tyson, and Hospice of Virginia. Each one of you represents clear and convincing evidence that God always places in our paths the right people at the right time.

I would like to give thanks to my brother Michael for his persistent and unwavering love and support of mom and dad throughout these last several years, providing so much more than me. And of course, I would like to thank mom for all you have done for dad to be all of the wife, partner, helpmate, caretaker, and friend that dad ever could have dreamed of. I have come to realize that most of the successes I have had in ministry came as a result of the knack I have of teaching myself how to do things, and that is clearly something I have inherited from mom.

It was literally overnight that my mother found herself having to learn how to operate a peg tube and become the caretaker for a man with a diagnosis that few study and fewer understand, but she, in addition to becoming a full-time caretaker also became a pharmacist, researcher, a fierce advocate, even more creative problem-solver, care coordinator, an expert in the complexities of the systems and processes of the Veterans Administration. If industriousness and hard work were all it took for one to be successful in this nation, today’s billionaire elite would all be working for my mom.

All of which brings me back to where I began. Dad was always such a believer that you do what you say you will do, and you keep your promises, and I promised that if I could make it this far, I would tell you dad’s favorite joke, so here it is.

There were once two old men who were the very best of friends named Bob and Jim. One thing that Bob and Jim had in common was a deep and abiding love of baseball. They played baseball together as children, they coached baseball together as young adults, and now, in the winter of their lives, they loved to sit together on the front porch of Jim’s farmhouse and listen to games on the radio.

As they grew older, like any of us, they began to think of their own mortality. This led them to reflect upon a great theological question: is there baseball in heaven? They both agreed that no matter what heaven was like, it would be much nicer if there were baseball there, so they hatched a plan. Whichever one of them died first would somehow find a way to return to earth and let the other know if there was indeed baseball in heaven.

A month later, Bob died, and a few weeks after that, Jim was sitting on the front porch, listening to a day game and missing his friend Bob. Just then, a strange, low, cloud appeared and began moving towards him. As it did, he heard a voice emanating from the cloud saying, “Jim! Jim!”

Jim asked, “Bob, is that you?”

The voice replied, “Yes, Jim, it is me. Bob! I have good news and bad news for you.”

Jim said, “What is the good news?”

“The good news is that there is baseball in heaven.”

“That’s wonderful!” said Jim, “But if that is the good news, what is the bad news?”

To this, Bob replied, “You’re scheduled to pitch on Tuesday!”

So dad, tonight, when you stand beneath those bright stadium lights and step onto the mound, just throw strikes, and don’t let anyone crowd your plate. Your shadows are in the bullpen, ready for whatever happens next.

Gloria In Excelsis Deo.

Margaret H said:

Doug, what a loving tribute to your Dad. Your family has been in my prayers. Best wishes on your new appointment.

Margaret Hamilton

LikeLike

psychicmilkshakea56adc51b9 said:

Amazing amalgamation of the loving essence of your Dad. I believe your Dad had his hand on your shoulder so you would make it to the end and tell his favorite joke!

Well done good and faithful son!

LikeLike